Katsushika Hokusai and Philipp Franz von Siebold

It might sound a little corny to say that artists live through their works, but in the case of Katsushika Hokusai (1760 – 1849), whose lengthy life story is mired in muddles, myths, and myriad name changes, it is his art that speaks with the clearest voice and provides the scale to weigh the words describing his life. This not only gives art historians and academics something to do, but also opens up and clarifies storylines in the life of the artist routinely hailed as Japan’s greatest.

The exhibition “Siebold & Hokusai and his Tradition” at the Edo–Tokyo Museum is a case in point. It centers around a highly likely though unconfirmed meeting of the great artist with Philipp Franz von Siebold (1796 – 1866), a German who served as physician to the Dutch trading post at Nagasaki from 1823 to 1829, when he was expelled accused of spying, who later became known for his books on Japanese flora, fauna, and ethnography.

The exhibition is divided into two parts. The first “Siebold and Hokusai,” curated by Dr. Matthi Forrer of Holland’s National Museum of Ethnology, Leiden, uses works from that collection and France’s Bibliotheque Nationale to make the case for the meeting. Most of the works are drawn from a series of hand paintings commissioned in 1822 by two Dutch visitors to Edo from the trading colony at Nagasaki, but collected four years later by Siebold and the colony’s CEO, Kapitan Willem de Sturler.

Sudden Rain in the Countryside

Intriguingly, a version of this meeting seems to have been recorded, although with some confusion over dates and details, by Edmond de Goncourt, the late 19th–century enthusiast of Japanese art. In his 1896 book Hokusai he mentions an apparent row over money between Hokusai and a doctor from the Dutch colony:

“Hokusai applied all his care and expertise to painting the four scrolls which were finished at the time when the Dutch would depart. And when Hokusai delivered his paintings, the kapitan gladly paid the agreed sum of money, but the doctor, pretending that his salary was lower than that of the kapitan, only wanted to pay half the money.”

Whatever the details, the result was that Siebold and de Sturler ended up with several dozen paintings on Dutch and Japanese paper that later found their way into the two respective collections.

The brief that Hokusai was given was apparently to depict normal people, objects, and various scenes designed to satisfy foreign ethnological curiosity. As a consequence, some of the paintings, like the realistically detailed “Various implements used with firearms,” look like they belong in a catalogue.

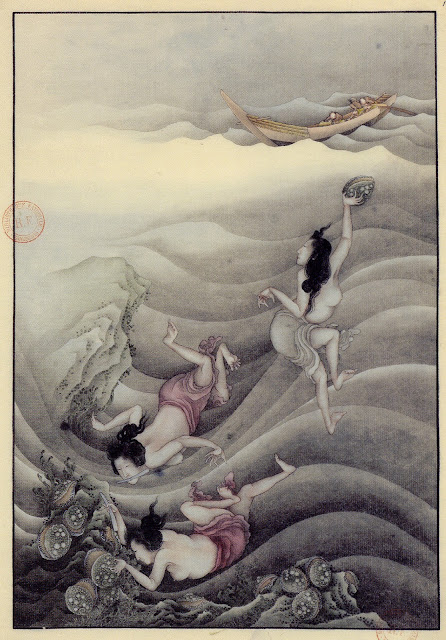

Others, like “Women Divers,” a painting in sumi ink and pigments, which imaginatively follows mermaid–like Ama divers down to the seabed, show much more artistic interpretation. This work in particular has a surreal dreamlike quality that must have impacted powerfully on the 19th–century European consciousness.

Women Divers

The exhibition also points to the influence of Western art on Hokusai. “New Year’s Day at Kasumigaseki” shows an obvious use of vanishing point, while even in “Running Horse Riders,” where the background is sketchy, Hokusai applies perspective to the horsemen whizzing by to help create a sense of centripetal dynamism.

We can infer from Hokusai’s often quoted summation of his lengthy career that the Dutch commission came at an important point in his career.

“Little of what I painted before my seventieth year was truly worth of note,” he wrote in the colophon of “One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji” when he was 75.

This was no idle sophism as most of the major series of prints for which he is remembered were produced after this commission, which came at a time when Hokusai’s career had entered artistic doldrums; he was spending less time on his art and more time writing senryu, the Japanese equivalent of the limerick. It may be possible, then, that the paintings the Kapitan paid for and Siebold haggled over acted as a spur to shake Hokusai free from a case of ‘artistic block.’

Whether this is true, the exhibition makes great efforts to show that many of the elements from these paintings later surfaced in his major print series, many of which can be seen in the second part of the exhibition.

For example, the horses and riders from “Running Horse Riders,” with their billowing garments and characteristic headgear were later transposed with some changes to “Sekiya Village on the Sumida River,” one of the classic scenes from “The Thirty–Six Views of Mount Fuji” (1831 – 34)” that can also be seen at the exhibition. Another example is “Sudden Rain in the Countryside” where the figures resisting the sudden squall and the trees bending to its force are close relatives to those in “Ejiri in Suruga Province” also from “The Thirty–Six Views.”

Ejiri in Suruga Province

This attention to detail makes this one of the most educational exhibitions on Hokusai in a long time. In its central thesis that a tight–fisted German doctor helped spur a talented artist to a new lease of life, it is certainly one of the most daring.

Colin Liddell

The Japan Times

20th December, 2007

The Japan Times

20th December, 2007

0 comments:

Post a Comment